Spring in Hokkaido

It's been quite a while since my last post here. Since then we have gotten another harvest under our belt, and made some serious moves toward setting up better post-harvest storage and milling infrastructure at the farmstead. I used my customary wintertime respite to work on ordering some more rice farming equipment from Japan, and in preparing for another short trip there to visit with some rice growing colleagues. I'm writing this post from my friend Takehiro Ono's house, in the little former Hokkaido coal mining town of Minami Bibai.

The landscape here is in some ways very reminiscent of the Champlain valley, with a broad agricultural plain and mountain ridges in the distance, much as the Greens and the Adirondacks form the two mountain walls running parallel to my own home. But in the foreground, you can see real differences, because here there is no gently sloping land to be found. Every arable acre has been divided into leveled parcels, usually surrounded with berms and serviced by irrigation and drainage systems.

Takehiro told me that the soil here is high in peat, and that in the earlier days of Hokkaido agriculture, water retention was a problem for rice agriculture, and considerable effort was made to amend the soil to help fields retain water better.

All told, Hokkaido is a very pleasant place, and at this point in the year is at almost exactly the same point in their spring as we Vermonters are in ours. The snow here is rapidly melting, and work is just ramping up to begin spring tillage work and get the large hoophouses that are used for rice nurseries covered. Snow loads here usually dictate that hoophouses have to be stripped of plastic over the winter, but from what I have heard, snow has been so light this year, maybe they could have been left on... There is some concern that the lack of thick snow pack in the mountains may mean less water later in the season.

I came directly from Burlington, Vermont to Sapporo, and Takehiro generously retrieved me at the airport and drove me to his charming house in Bibai. Takehiro worked for Bibai City in the tourism division and is about to head overseas himself to join his wife in Thailand for a while. I was lucky enough to be able to come visit with him here during the interval after the completion of his contract with the city but before his departure.

Yesterday we met with Yoshikazu Orisaka, who is a veteran duck rice agriculture practitioner in Urausu, a village near Bibai. My father and I met him previously in 2015, during our last visit. Orisaka was eager to help me with technical questions about the equipment I am in the process of importing. It's interesting how huge the spread in cost is between what new equipment costs here and what it sells for on the used local market.

Swans stopping over in Bibai, on their migration to Siberia.

We all ran out of energy for this conversation before I ran out of questions, as it is a lot of work to convey this information across the language divide. At this point I can bash out some simple sentences in Japanese with my limited rice-farming vocabulary, which is very gratifying to me when it works, and maybe this demonstrates seriousness and commitment to my hosts, but the actual usefulness of my conversation skills is still sadly limited.

Afterwards, Takehiro and I left and had a nice lunch at an Udon (noodle) joint and hit some industrial clothing supply places to look for rice paddy boots and other rice farming gear small enough to bring back home in my luggage. I also picked up some rice bowls and the 100 yen shop.

As a last stop for the day we drove to the town of Iwamizawa, where I knew there was a used farm equipment supply place. We had actually stopped in two years ago and scoped out the machinery, but everybody was at lunch or something to that effect. However, we poked around and I quickly realized that used farm equipment here is much more affordable than I had ever thought possible.

The original inspiration for visiting Japan was to connect with fellow practitioners of integrated duck and rice agriculture, but discovering that this equipment is affordable and accessible (though it is a LOT of work and expense to get it back to New England) was a very important secondary accomplishment. Anyway, this time there was somebody at the yard to talk to, and he seemed quite eager and willing to help source the kind of equipment that we small scale rice farmers are after, and it could be an important breakthrough to make a personal connection to a supplier who understands farm equipment well and is willing to work with the various requirements of American importers. It is quite possible that we will be able to give them some business, both for my own farm and for other American startup rice operations that I am involved in and am trying to support in various ways.

The siginificant thing about this kind of equipment is that it is designed for an environment where labor constraints roughly correspond to the situation in the United States. In other words, this equipment makes it possible for a relatively small workforce to undertake what I would call "community-scale" commercial operations (say, from 2 to 20 acres) with a fairly modest capital outlay that can be easily paid down over time. While it is possible to produce rice with basic hand tools only, doing it this way will set some significant limits on the net productivity of any rice farm, and doing everything by hand means pretty hard work that is unevenly distributed throughout the season. There are surges in labor needs at transplanting (in June) and at harvest (in late September or early October) that are, in most cases, likely to very hard for small-scale American farmers to be able to meet.

As an example, transplanting an acre of rice takes ten people one day if they are fast and skilled. For most American transplanters without conditioning or training, it is better to allow twenty people. This is a serious commitment of time and/or money that would probably rule out rice as a commercial crop for all but the most committed, and would likely drive up the cost of the finished product well beyond the range of ordinary staple food items in the U.S. local and organic market. I can't speak for everyone who has an interest in growing rice, but for me, one of the main goals of my work with rice is to provide food to neighbors at a reasonable cost. So, if labor requirements are very significant, this presents a problem.

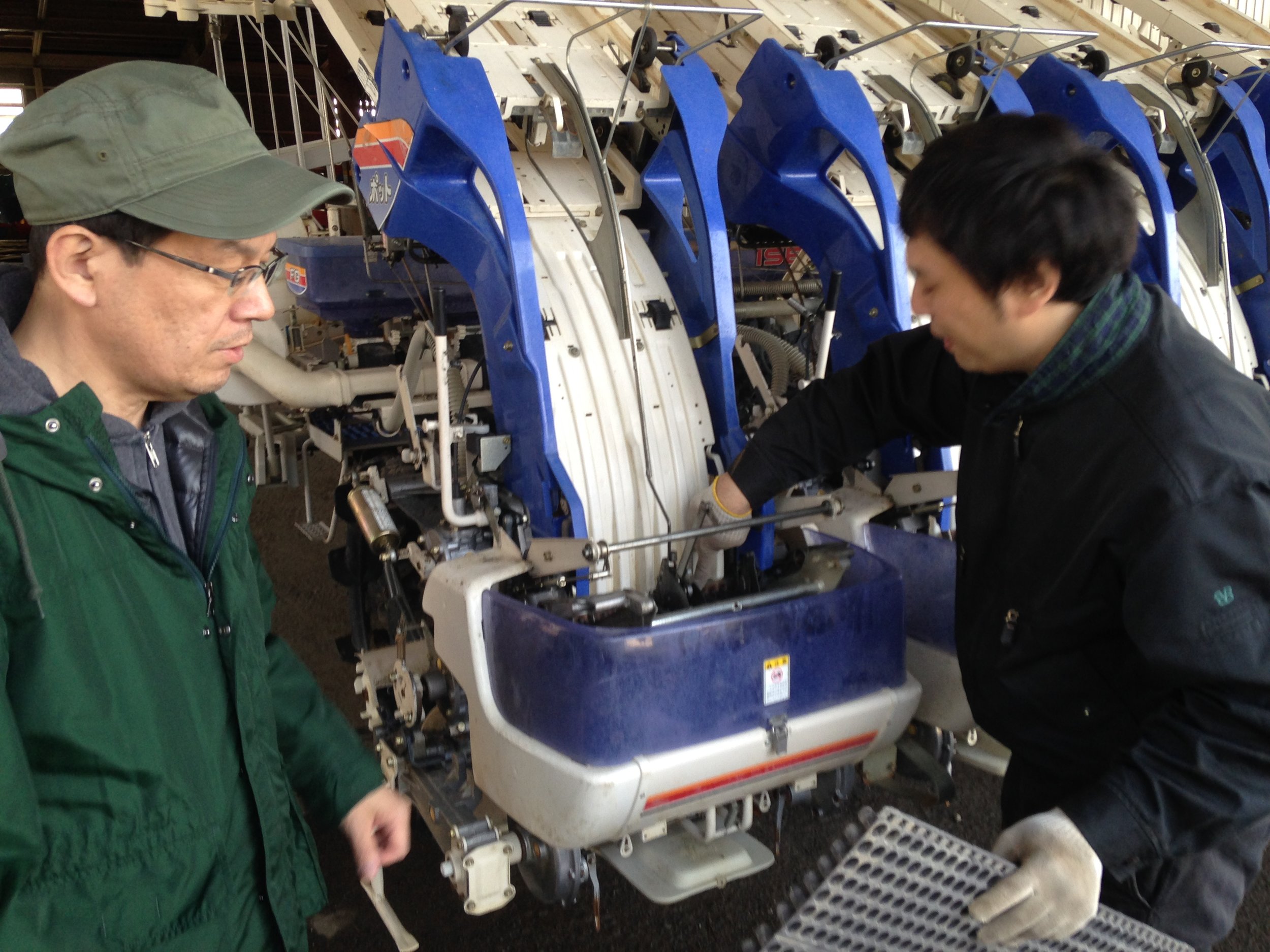

Mr. Ashihara, a techinician for JA Hokkaido / Hokkuren in Iwamizawa shows the mechanism of a "pot-type" rice transplanter to me and Takehiro Ono.

Enter the transplanter. On the used market, small transplanters cost under $1000 US, and one transplanter can transplant an acre per day with one or two people running it. The labor savings easily justify the purchase and maintenance of the equipment--and even if we allow a second $1000 to get the transplanter into the country the overall cost is still just $2000, and if each paid person in the field manually transplanting costs $100 per day, time 20 is $2000 in labor for just one transplanting season. This little machine could pay for itself the first year.

When I first got into farming, part of my interest was in finding ways to do as much work by hand or by animal power as possible. I still enjoy physical work and am striving to maintain a place for it, and for the use of direct elemental power from wind a role as well. However I am not getting any younger, and over time my determination to turn back the clock and reinvent the relationship between farming and physical work has given way somewhat to a desire to see this kind of work advance and thrive in the world as it is now, a world in which we farmers are shorthanded and busy and doing too many jobs.

Circumstances are not so different here on Japan's northern island, where I see a sort of reflection of myself in the farmers like Orisaka-san, doing a lot of work alone, or with just a little outside help. I am glad to have a connection to this part of the world. It is a real pleasure to see some friends from the last visit and to make some new ones, and to see flowers begin to push young shoots through the soil in this exotic yet strangely familiar place.